1.0 INTRODUCTION

Education, has since time immemorial, been the vehicle with which humanity transcends mediocrity and into development. Education is an important tool that plays a huge role in this modern and industrialized world. It provides people with knowledge, skill, technique, information, enabling them to know their rights and duties toward their family, society as well as the nation. In essence, education shapes human’s general, physical, psychological, moral, intellectual, and social development. Research indicates that, worldwide, people who have higher levels of education have greater opportunities for employment and earn higher incomes ( Jensen , 2009 ). It is therefore a primal essence and a sine qua non to the survival of every race and people.

A landlocked country in northwestern Africa, Burkina Faso is one of the poorest and most illiterate countries in the world. According to United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2018) the adult literacy rate (ages 15 years and older) in 2018 was approximately 41.22%. While the male literacy rate is 50.07%, for females is 32.69%, showing a big gap between the sexes. For the 2010-2011 school year, 61% of school age children were enrolled in primary school in Burkina Faso (UNICEF, 2012). In this article, I will introduce Burkina Faso's education from Burkina Faso's educational history and policies, educational structure, challenges to education, measures to overcome educational challenges, and education in Burkina Faso during COVID-19.

Source: https://www.losservation.org

source: https://www .globalpartnership.org

2.0 EDUCATIONAL HISTORY AND POLICIES IN BURKINA FASO

2.1 Educational History

The resulting policy document, however, was never implemented because it was considered too superficial. In the 1960s, the idea that youths should obtain more knowledge about agriculture in order to increase production became popular. From 1967 onwards so-called CERs (Centres Education Ruraux or “rural education centres”) were opened, where 3 year programmes were taught in agricultural education. The initiative, however, was abandoned when an evaluation in 1970 indicated that the programme had only reached 20% of the 136.000 youths who were targeted [Kobiano 2006:46]. From 1971 to 1980 number of children who started going to school increased slowly, which was at least partly due to external funding. Half way through the 1980s, there was another significant growth in enrolment numbers. As part of the revolutionary policies, between 1983 and 1987, 22.379 new classrooms were built (compared to 1884 between 1969 and 1983). An obligatory national service obliged people to teach in rural areas and many new teachers were recruited and employed after only a few months of training. Between 1982 and 1990, enrolment rates rose from 16% to 30%, yet a decline in quality of teaching is likely to have occurred due to the low qualification requirements for teachers [Kobiano 2006:45]. During the structural adjustment programmes (SAP) that started in the early 1990s, investments were made by international institutions to improve the supply of education mainly by recruiting and educating teachers. Foreign debt negatively influenced educational outcomes yet it should be taken into account that Burkina's SAP programme was of the “second generation”, in a period when international institutions started to recognise the harmful social effects of the adjustment programmes (idem). The simultaneous impoverishment and the decline in formal employment opportunities diminished the demand for education [Kazianga 2004]. Low attendance, low quality, and inadequate management schemes have characterised the situation since the nineties. Alternatives were formulated, of which the bisongo (pre-school), satellite schools (classes in remote areas) and non-formal basic education centres can be considered most significant. In 1996, a special action plan for girls was put in place by the government, with the aim to raise enrolment of girls, keep them in school and let them succeed. A special board for girls' education, Direction de la Promotion de l'Education des Filles (DPEF), was set up.

2.2 Overview of Educational policy

Not much is known about traditional forms of education that existed in the country before the French colonisation and arrival of Christian missionaries around 1900, but it can be assumed that the first literacy education was introduced by Muslims several centuries ago. With Islamic expansion in West-Africa, rural institutions were set up, combining elementary Islamic education and farm production [Saul 1984:71]. Christian missionaries introduced the first western style schools. The French colonisers invested only marginally in formal education in the then Upper Volta, because the area was mainly considered a labour reserve for the richer, coastal areas of Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire. In order to educate local administrators, the French focused on chiefs' sons. In contrast to the colonizers, missionaries also endeavored to educate girls, because they had a different interest, namely educating good Christians.

During the colonial period (last decade of the 19th century to the independence of the country in 1960) the educational system and the curricula were a replica of the French educational system. At independence in 1960, school enrolment rates were consistently low at 6.7%. Between 1960 and 1966, there was a growth to 10.5% (from 51.000 to 98.000). The subsequent stagnation in growth has been attributed to the cutting in public spending by the government so-called self-adjustment and the government's decision to stop subsidising Christian institutions [Kobiano 2006:61]. Yet since independence the focus has been on more than just the numbers of children in school. Since then, several policies have been undertaken to address problems in terms of quality teaching as well as relevance of curriculum. Just after independence, concerns were expressed for a curriculum reform that would do justice to the new geographical, historical and cultural reality.

In 1962 the curriculum was slightly revised, but it was only between 1974 and 1984 that the country really launched a major reform of its educational system. Among other innovations we can mention the introduction of local languages, productive work and an emphasis on community involvement. The results of the experimentation seemed promising but it was abruptly ended in 1984 by a political decision of the then revolutionary regime of the country.

A reform project called the Burkinabe revolutionary school system was designed in 1986 and it was supposed to be implemented straight away without any form of experimentation. It included quite a few radical ideas such as introducing English as a foreign language alongside French as well as computer science in primary school and the elimination of diplomas. For some undisclosed reasons the project was quickly shelved.

In 1994, some seven years after the end of the revolution, the country called a huge national forum on education (Les Etats Generaux de Education) [States General of education] attended by representatives of all stakeholders to diagnose the problems of the educational system and propose new orientations. The recommendations of this forum were translated into an education orientation law (Loi d'orientation de l'Education ) adopted in 1996. This law was further specified by an education policy letter in 2001. Another forum on education was held in 2002.

The most important development resulting from the States General was the ten year basic education development plan (PDDEB) (Plan Decennal de Developpment de l'Education 2001-2010). The first phase of the plan ended in 2006 and the second phase is now being implemented alongside a general reform launched in 2007. The 1996 Education Orientation Law (Loi d'orientation de l'Education ) was replaced by a new law (Loi Portant Loi d'Orientation de l'Education) adopted by the National Assembly on 30 July 2007 and promulgated on 5 September 2007.

The law clearly states that access to basic education is free and compulsory and must be provided to every child aged 6 to 16 living in Burkina Faso regardless of sex, race, creed, social origin, political opinions, nationality or physical condition. It specifies the goals and objectives of education in the country. It also describes the structure of the educational system, and it even takes a stance on some hot issues such as the languages of school (French and national languages). The law was further explained in the government letter on Education Policy (Lettre de Politique Educative).

2.3 Recent Educational policies: PRSP and PDDEB

In 2000, Burkina Faso became one of the first developing countries to prepare a full Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP), which was updated for the 2004-2006 period. The Ten Year Basic Education Development Plan (PDDEB) (2001-2010) was designed to implement the PRSP in the education domain. PDDEB aims at solving the problems of access, quality and management of the educational system in order to reach the Millennium Development Goals and fight against poverty. PDDEB therefore has quantitative, qualitative and institutional objectives, among which we can mention:

i. raising the primary school enrolment rate to 70% by 2010 with a particular effort to reduce gender and regional disparities;

ii. Diversifying educational formulas through experiments such as Satellite proximity Schools, Non-formal basic education centres (CPAF and CEBNF), bilingual education using French and national languages, modern Franco-Arabic schools, etc;

iii. Raising the country's literacy rate to 40% by 2010 by developing and diversifying adult literacy programmes;

iv. Improving the quality and relevance of basic education by improving the training of teachers and their pedagogic supervisors, improving learning/teaching conditions and setting up a permanent monitoring of education quality;

v. Diversifying post-literacy programmes in national languages and in French for better training of and information for adult learners;

vi. Improving the control, management and evaluation of the educational system through capacity building, in-service training of the personnel, the development of information and applied research.

PDDEB has been operational since 2002 and despite a few administrative problems that have delayed the implementation of some of its programmes, its results are now being felt on the field: a significant number of new schools were built to improve access, and large-scale practical measures were taken to improve learning conditions (school canteens, free distribution of textbooks and school supplies, incentives to increase gender parity in schools, etc.).

3.0 EDUCATIONAL STRUCTURE IN BURKINA FASO

The education structure in Burkina Faso is organised into formal and non-formal education sub�systems. The official language for education is French and so education is mainly conducted in French, which only 15% of Burkinabe can speak, rather than in first languages of the country .

3.1 Formal education

The formal education in Burkina Faso is structured into basic education (6 years), lower secondary (4 years), upper secondary (4+3=7) and tertiary education.

3.1.1 Basic education

Basic education comprises preschool education (for children aged 3-6 years) and primary schools (that accept children between 6-13 years old). Primary schools are dived in 3 cycles: the preparatory course (CP1 and CP2), the elementary courses (CE1 and CE2) and the middle course (CM1 and CM2), which is finalised with a certificate (CEP) that is needed to continue to secondary education. Primary schools are often, especially in rural areas, organised into a “multi-grade” system. A return to this “classical system” (that existed in the 1980s) is now officially being encouraged. It entails enrolling pupils only once every 2 years, and thus grouping two age groups into one class; this is done due to the lack of teachers. In urban areas, where enrolment rates are much higher and more teachers are available, the double stream system is sometimes used whereby each grade has several classes and teachers. The MEBA (National Department of Basic Education and Literacy) is in charge of the education of primary teachers in 5 so-called ENEPs Teacher Training Colleges.

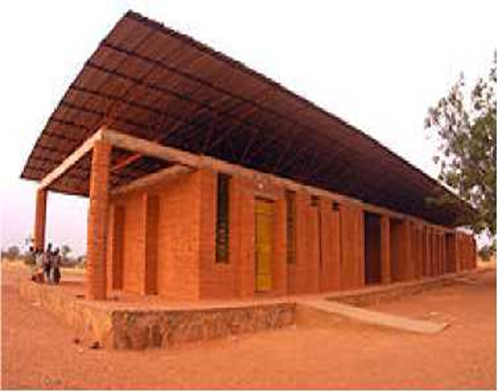

Primary school in Gando, Burkina Faso source: https://www.blaisecompaore.com

Source: https://www.wikipedia.org

3.1.2 Secondary education

There are two types of secondary education: general education and technical & professional education. The large majority of secondary students are in general education. In general education, the first cycle of four years is finalised with an exam Premier Cycle: BEPC (Brevet d'Etudes du). The BEPC certificate is the minimum requirement for admission to the (selection process for) certain tertiary institutions including Teacher Training College and Nursing College. The second cycle of (general) secondary education lasts another three years and is concluded by the BAC exam (le Baccalaureate), which provides access to university. There are three types of formal technical & professional secondary education. The first type takes 3 to 4 years and results in the CAP (Certificate d'Aptitudes Profesionnelles). The second type starts with the BEPC and then takes 2 years, resulting in the BEP (Brevet Etudes Profesionnelles). The third type also starts with the BEPC and then takes 3 years, resulting in the BAC (le Baccalaureate).

3.1.3 School sessions

School days are Monday to Wednesday and Friday and Saturday. Thus, a week runs from Monday to Saturday, with the schools closed on Thursday. School hours are 7.30-12.30 and 15.00-17.00. The “long vac” officially runs from mid-July to September. In reality, especially in many rural areas, primary schools stop teaching 1-2 months earlier and the actual holiday coincides largely with the yearly rainy season when the bulk of the farming and herding work has to be done.

3.1.4 Tertiary and higher education

Higher education comprises a first cycle of two years leading to a general university diploma (DEUG), a second cycle of two (2) years ending in the Masters and a third cycle of variable duration that could lead up to the Doctorat d'Etat. As of 2010 there were three main public universities in Burkina Faso: The Polytechnic University of Bobo-Dioulasso, the University of Koudougou and the University of Ouagadougou. The first private higher education institution was established in 1992 and the Universite Libre de Ouagadougou began operations in 2000. The Universite Catholique de l'Afrique de l'Ouest opened its Burkina campus in Bobo-Dioulasso in 2000 with a food and agriculture speciality, and the Catholic Universite Saint-Thomas-d'Aquin in 2004 in Ouagadougou. Supervision rates are different from one university to another. At the University of Ouagadougou there is one lecturer for every 24 students, while at The Polytechnic University of Bobo-Dioulasso they have one lecturer for every three students.

Higher education provision is highly centralized in Ouagadougou. In 2010/2011 the University of Ouagadougou had around 40,000 students (83% of the national population of university students), the University of Koudougou had 5,600 students, and the Polytechnic University of Bobo-Dioulasso had 2,600. The private universities each had less than 1,000 students. In Burkina Faso, no public school ranks higher than the Time Higher World Universities, probably because the teaching language of the school is French, so the school can receive a lot of international assistance in public education, and the class size of the school is large in major public universities. In addition, the students of the school also have the opportunity to study until the doctoral level.

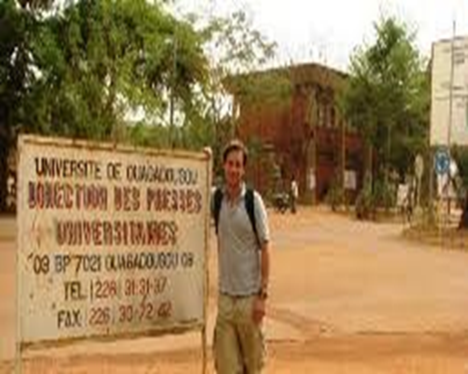

University of Ouagadougou

Source: https://www.wikipedia.org

source : https://www.scholaro.com

3.1.5 Free Access to Primary

School International treaties have recognised free and compulsory elementary education as a human right for more than half a century now, and especially during the last decade the drive for universal (primary) education has gained momentum. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), agreed upon in 2000, set 2015 as the year in which universal primary education (MDG-2) is to be achieved. The Education Act in Burkina Faso makes schooling compulsory from age 6 to 16. Despite such efforts and their echoes in national policies, dropout rates are high, however, as are the number of students repeating a grade .Primary education is supposed to be free and compulsory but those stipulations are not always adhered to. Approximately 66% of the children in Burkina Faso have access to primary education and 17% have access to secondary school (Hernandez, 2012).

3.2 Informal education

In Burkina Faso, the non-formal education system serves as a means of alternative education opportunities for children who never went to school or have dropped out and illiterate adults. These alternatives need to be developed because not all children go to school (the attendance rate is 85%) and more than 40 children in 100 drop out before finishing their six years of schooling (the completion rate is 60%). Alternative education opportunities include school-based literacy, simple technical training courses and developing a literate environment that is providing access to reading materials. The goal is to help people gain access to literacy and education to develop skills and knowledge that are useful in their communities. The target group is children aged nine to fourteen who have not had the chance to go to formal school or who had to leave school very early. After four years of basic education they are given an assessment. There are gateways for those wishing to go on to formal school, making it possible to study up to university level. For the others, there are professional training courses or apprenticeships at agriculture training centres where they can learn to manage stock farming and become arable farmers. Through its support for the National Fund for Literacy and Non-Formal Education (FONAENF), which is a partner of the PAEB, the SDC has helped achieve several objectives and marked improvements in Burkina Faso's education system. Since 2006, 10,000 children (45% of whom were girls aged nine to fifteen who had never been to school or had dropped out) have received education and training in certain trades thanks to the development of innovative alternatives to formal schooling. The success rate for pupils in the non-formal education system rose from 92% in 2012 to 96% in 2015. More than 3.2 million textbooks written in the country's national languages were produced and distributed. Since 2006, these textbooks have boosted pupils' learning and prevented their falling back into a life of illiteracy.

Source : https://www.compassion.com

4.0 CHALLENGES OF EDUCATION SYSTEM IN BURKINA FASO

Burkina Faso is one of many countries that encounter a plethora of difficulties in educating their children, facing barriers ranging from poverty, Child labour, Disparities in Access to School and Distribution of Infrastructures, Inadequate Technical Education and Vocational Training System, Health and nutrition as well as Government Policy and biases to insufficient resources and revenue necessary to provide a quality education to the multitude of children who need it.

4.1. High level of Poverty

The high poverty level in Burkina Faso is one of the key challenges of education in Burkina Faso , accounting for why the majority of people do not have a sixth-grade education . Due to extensive poverty in Burkina Faso, people are more concerned with meeting their essential life needs than with educating their children, which is not perceived as a crucial need. In addition, if family finances are scarce, a common occurrence in Burkina Faso, parents cannot afford to send their children to school while simultaneously providing for their families. Most people, including children, eat one meal a day because that is what is usually available and what they can afford. If food is available at school, parents are more likely to send their children to school, but a government program designed to provide free meals for children in all public schools in Burkina Faso does not exist.

4.2 Child labour

Another limitation of education in Burkina Faso is Child labour. Access to education is a fundamental necessity for children if they are to reach. It is a common practice in Burkina Faso for parents to hold their children back from attending school or refuse to enroll their children in school. Children are regarded as free labor in the family, and if all the children go to school, there is no one to help with chores related to running the family farm or a family business.

4.3 Disparities in Access to School and Distribution of Infrastructures

Gender display also plays a role in access to education in Burkina Faso. Early marriages tend to force most girls out of school in Burkina Faso. Some communities view girls as a source of “income” and others are married off due to the patriarchal values that govern their communities. According to United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2018) the adult literacy rate (ages 15 years and older) in 2018 was approximately 41.22%. While the male literacy rate is 50.07%, for females is 32.69%, showing a big gap between the sexes.

4.4 Health and nutrition.

Health issues including HIV/AIDS, pre-marital sex, early and forced marriage, unwanted pregnancy, food security, malnutrition, school-feeding programs, access to potable water, diseases transmitted by unclean water, childhood diseases, malaria present a significant barrier to education in Burkina Faso. In rural areas, where the majority of the population live, up to 60% of the drinking water was found to be contaminated at levels exceeding the recommendation of WHO (2013). It is common for families to have to travel long distances to obtain water that is safe for human consumption, regardless of whether they live in an urban or rural location. Many villages do not have a well or a “tap” and family members often leave in the early hours of the morning in order to arrive at the well site before other families. A lack of fresh, clean drinking water is a barrier to education in that the responsibility of obtaining clean water is frequently given to children, which concurrently causes them to miss a day of school yet drinking unclean water may result in missed days of school due to water-borne illnesses. In essence, the spread of the AIDS pandemic and other high prevalence diseases has resulted not only does the reduction in the life span limit the benefits from the investment in education, but it also threatens the very effectiveness of the educational system in view of the increase in the absenteeism of teachers and pupils, the need to replace sick teachers and the growing number of child orphans. All these effects equally render the management of the educational system complex.

4.5 Inadequate Technical Education and Vocational Training System

Technical and vocational training is more theoretical than practical and is carried out without an effective linkage with the labour market. This situation has resulted in excessive unemployment of young graduates; the high tendency by holders of the CAP or BEP to further their studies; the virtual non-existence of self-employment, which is perceived by young graduates as a sign of failure. Vocational training comes under different ministries, thus limiting its visibility, which does not make for an overall consistency. Furthermore, there is no efficient institutional and organizational framework that would foster a better training/employment linkage. These lapses are compounded by constraints relating to the highly limited financial resources (2% of the education budget is allocated to technical and vocational education) for initial training and a lack of a management mechanism for the continuing education tax paid by enterprises. This represents an estimated CFAF 2.5 billion per annum.

4.5 Government Policy

Policy and development regarding governance of Burkina Faso is the responsibility of the central government. Government officials make all the decisions concerning the education of children in Burkina Faso however, not all the legislation passed by lawmakers is implemented uniformly across the country or enforced. Consequently, some children are prevented from attending school due to problems related to policy and development over which they or their parents have any control. Moreover, the challenge of providing free education for all children in Burkina Faso is that fiscal appropriation is drawn from limited revenue. Money allocated for education in 2015 was 18.8% of the total budget, 2.89.7 billion CFA, or about $502,860,000 (US) (Universalia, 2018). The implication is that there may be insufficient funds available to provide free education for all children in Burkina Faso and that families will still have to afford school fees if they send their children to school

5.0. POLICY MEASURES TO COMBAT THE CHALLENGES

The government has continued to commit to developing effective education strategies and to solve the above challenges. The progress of Burkinabe’s education system entails addressing several challenges. These policy measures can be grouped under the input factors as follows:

5.1Material inputs:

Buildings, seats, faculty housing, water points, latrines

Books and school supplies

School means and foodstuff

Health, nutrition, hygiene

5.2 Human resources :

Pre-service and in-service training of teachers and pedagogic supervisors

Capacity development for the management and monitoring of the system

Training of textbook writers and syllabus designers

5.3 Other inputs :

l Curricular reforms

l Measures to increase teaching time

l Framework for fighting against the HIV-AIDS pandemic

l Decentralization

l Official guidelines and legal texts

l Incentives to motive teachers and pupils

6.0. Education in Burkina Faso during COVID-19

6.1 OVERVIEW of COVID-19 in BURKINA FAS

Since the start of the outbreak in December 2019, the new coronavirus (COVID-19) has spread to nearly all countries and territories and so Burkina Faso is no exception. The first case of COVID-19 in Burkina Faso was detected on 9th March, 2020 in Ouagadougou and so on 10 March,2020, the government officially declared COVID-19 an epidemic (UNICEF 24/06/2020). The death of Rose Marie Compaore , a member of Burkina Faso on 18th March, 2020 marked the first recorded fatality due to covid-19 IN Sub-Saharan Africa. As at 26th July, 2021 13,541 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in all the thirteen regions of Burkina Faso, including 169 deaths, and a total of 37,120 vaccine doses have administered. (WHO 26/07/2021).

6.2 Containment measures

Following the official declaration of COVID-19 a epidemic on 10th March, 2020, to contain the spread, the government announced the closure of all schools and universities in the country on 15th March,2020. This was followed by a ban on public gatherings, including demonstrations and religious services, a curfew, border closures, and the closure of Ouagadougou’s market. Ouagadougou, Bobo Dioulasso, Dedougou, Hounde, Banfora, Manga and Zorgho were quarantined, with travel to and from those cities forbidden.

6.3 Effect On Education

In an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19 the government of Burkina Faso ordered the closure of all schools and so by 16th March,2020 all the schools were closed (more than 20,000), affecting more than 4.2 million students. On 1 July,2020 approximately 800,000 students in exam years returned to class. The 4.2 million students who are not in an exam year were to remain out of school until 1st October,2020 at the earliest. The gross enrolment rate declined for the third consecutive year by 2.2 points between 2018/2019 and 2019/2020. The primary school completion rate also declined by 3.1 percentage points, from 27.8% in 2017/2018 to 18.8% in 2018/2019 and then to 16.9% in 2019-2020。

While there has been an effort to provide out of school students with opportunities for distance learning through radio broadcasts, television shows and online classes, only around 118,000 (2.36% of affected children) had benefitted from those initiatives by June,2020 (Education Cluster 18/06/2020, MENA 29/05/2020, Burkina 24 27/05/2020).

6.4 UNICEF’s COVID-19 response

In response to the closure of schools on 16 March, 2021 affecting more than 4.2 million students, The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) put in place mitigation actions, notably the scale up of the Radio education programmes at national level. So far, 94,683 (49,235 girls) students from pre-primary and primary schools benefited from distance learning via radio and TV.

Simultaneously, With UNICEF support, 125,000 posters including 3,500 in national languages to raise awareness against COVID-19 were delivered to the Ministry of national education, literacy and promotion of national languages (MENAPNL) and NGOs. As at the of end October, 2020 UNICEF and its partners reached 232,946 children (114,143 girls - 49 per cent) with educational interventions in the Centre–Nord and Sahel regions through:

• Back-to-school campaigns, school supply distribution and the provision of tables benches for classrooms for 14,962 out-of-school children (7,357 girls - 49 cent).

• Radio education program for 202,532 children

• 609,090 children (girls 314,339 - 51.6 per cent) reached for life-skills education activities though radio education program since April in response to the closure of schools due to COVID-19 pandemic.

Further, by July,2021 UNICEF had received US$500,000 for COVID-19 response from USAID, US$350,000 from UK DFID, US$856,443 from CERF, US$70,000 from Global Partnership for Education (GPE), US$300,000 from Education Cannot Wait and US$1,100,000 from DANIDA (Denmark) for activities related to C4D, health, WASH, nutrition, education, child protection, communications, supply and coordination. Additional funds are being negotiated with a range of donors.

Source : https://www.globalpartnership.org

source : https://www.ipsnews.net

(Osei Simon Peter,Assistant Researcher of CWAS,School of Public Affairs and Administration of UESTC)

Please refer to the Chinese Version published on Huanqiu.com, one of the top three rating news media in China. Huanqiu.com is a national rating on line media platform, approved by the publisher of People's Daily and the Central Internet Information Office of China. This column is to provide a platform for researchers and practitioners on West African issues.

Link:https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/44KnPjX4GMe