LINK:https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/49HyaxdrLfn

Koffi Dumor:The fall and rise of Ghana's debt: some alternatives

By 2000, the Ghanaian government had borrowed so much money that the nation was in dire financial straits. It then joined the initiative of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank for heavily indebted countries. Consequently, creditors wiped off a significant portion of the country's nearly $4 billion in foreign debt. In 2006, when the effort concluded, Ghana's entire governmental debt amounted to $780 million (25 percent of GDP). Since then, the debt stock has increased by 7,000% to $54 billion, or 78 percent of GDP. The current debt ratio to GDP is 78%, while the average for developing nations is 60%.

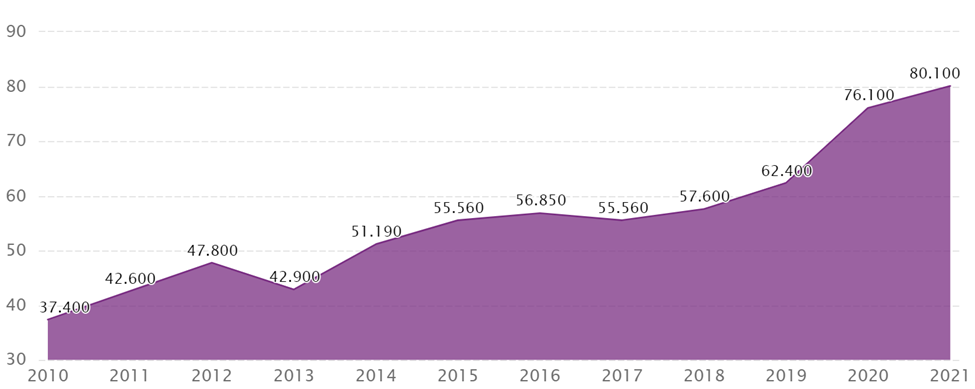

From 2006 through 2021, the chart displays Ghana's Government Debt as a % of

Authors from https://www.ceicdata.com/

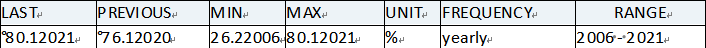

What was Ghana's Government Debt: % of GDP in 2021?、

In Dec 2021, the Ghanaian government's debt was 80.1% of the country's nominal GDP, compared to 76.1 % in the prior year. See the table below for further information.

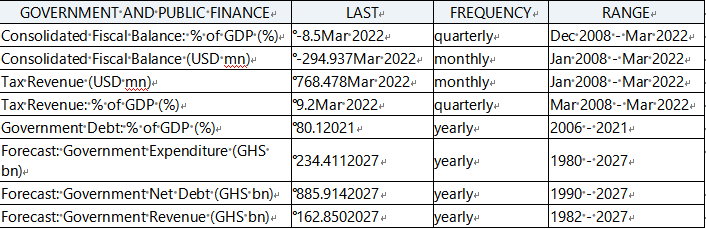

Ghana Key Series

Comprises 36 key indicators produced by CEIC specialists for Ghana.

How did Ghana get into this point?

Since the closure of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries program in 2006, the public debt stock has been primarily driven by the buildup of budget deficits (48.6%), currency devaluation (28.2%), and off-budget borrowings (23.2 percent ). Ghana's debt stock rose astronomically between 2017 and 2019 for three reasons beyond the common factors.

First was the country's debt in the energy sector6. This debt is owing to the nation's electricity producers and suppliers. It has been accrued mostly by Ghana's state-owned corporations, which struggle to produce sufficient internal revenues to pay back their loans. For example, the government offered a $3 billion bailout in 2021.

The second was the country's central bank initiative to clean up the financial system. The Bank of Ghana withdrew the licenses of many banks, savings and loans, microfinance organizations, finance houses, and investment institutions between 2017 and 2019, owing to their bankruptcy and financial misconduct. The government had to issue an additional $3 billion in bonds to reimburse banks, financial institutions, and clients.

Thirdly, COVID-19 has seriously affected the Ghanaian economy owing to lockdowns, border closures, limitations on mobility, and the decline in crude oil prices, as it has affected the economies of many other nations. The economic constraints caused a $2 billion decline in revenues, while COVID-19 expenditures raised overall government spending by $1.7 billion, for a total fiscal effect of almost $4 billion in 2020.

How bad is it?

The existing tightness of the Ghanaian budget prevents the government from doing anything without borrowing. Rigidity refers to mandatory budget contributions over which the government has no authority. Only two mandatory payments (employee salaries and debt servicing) devour the whole income and grants. In 2020, debt servicing (interest and amortization) consumed 70 % of total revenue. This is close to 72 % when the nation joined the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries program.

Based on the forecasted income and spending statistics in the budgets for 2021 and 2022, the debt service burden is projected to increase to 82% in 2021 before decreasing to 45% in 2022.

Borrowing will be necessary for the government to cover the remaining statutory expenses and all other discretionary expenditures. If the government fails to impose discipline, increase domestic income, or reduce spending (or both) to generate fiscal space, it will be forced to seek assistance from an International Monetary Fund program.

Several foreign credit rating organizations have recently downgraded Ghana's economy, citing its inability to generate enough cash to cover its debt. This signal to investors is that Ghana's government bond is unprofitable, and its default risk is too high.

This implies that the government may be unable to raise funds on the international financial market. The alternatives are either to borrow domestically, drive out the private sector, or borrow from other nations. If this option has been exhausted, the country must apply for a program via the International Monetary Fund.

What effect has this had on the economy?

As a result of the country's massive public debt and sluggish income growth, it must borrow to support its expenditures. Until the government borrows funds, it is essentially powerless. This has impeded the government's capacity to execute its plans and policies for economic growth, transformation, and job creation.

Over 16 years (2006-2021), the extractive industry was the primary driver of the country's economic development. This industry is capital-intensive, employing more machines than people. The result is that, while there is some economic growth, it is not derived from employment-generating areas of the economy. This is the reason why unemployment has soared4 from 5% to 13%.

Exit possible solutions?

Ghana is now in a precarious situation. The only solution is to generate sufficient income to fund its development. Even if the government could borrow, it would still need to boost domestic income to pay down the debt. Therefore, there is no alternative for mobilizing domestic resources. $6 billion is the expected budget shortfall for 2022. The government must collect money via taxation (without overburdening taxpayers) and other means.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies conducted research1 on the government's income streams in 2018 and produced the following suggestions for future yearly revenue increases for Ghana's public finances:

How did Ghana get into this point?

Since the closure of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries program in 2006, the public debt stock has been primarily driven by the buildup of budget deficits (48.6%), currency devaluation (28.2%), and off-budget borrowings (23.2 percent ). Ghana's debt stock rose astronomically between 2017 and 2019 for three reasons beyond the common factors.

First was the country's debt in the energy sector6. This debt is owing to the nation's electricity producers and suppliers. It has been accrued mostly by Ghana's state-owned corporations, which struggle to produce sufficient internal revenues to pay back their loans. For example, the government offered a $3 billion bailout in 2021.

The second was the country's central bank initiative to clean up the financial system. The Bank of Ghana withdrew the licenses of many banks, savings and loans, microfinance organizations, finance houses, and investment institutions between 2017 and 2019, owing to their bankruptcy and financial misconduct. The government had to issue an additional $3 billion in bonds to reimburse banks, financial institutions, and clients.

Thirdly, COVID-19 has seriously affected the Ghanaian economy owing to lockdowns, border closures, limitations on mobility, and the decline in crude oil prices, as it has affected the economies of many other nations. The economic constraints caused a $2 billion decline in revenues, while COVID-19 expenditures raised overall government spending by $1.7 billion, for a total fiscal effect of almost $4 billion in 2020.

How bad is it?

The existing tightness of the Ghanaian budget prevents the government from doing anything without borrowing. Rigidity refers to mandatory budget contributions over which the government has no authority. Only two mandatory payments (employee salaries and debt servicing) devour the whole income and grants. In 2020, debt servicing (interest and amortization) consumed 70 % of total revenue. This is close to 72 % when the nation joined the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries program.

Based on the forecasted income and spending statistics in the budgets for 2021 and 2022, the debt service burden is projected to increase to 82% in 2021 before decreasing to 45% in 2022.

Borrowing will be necessary for the government to cover the remaining statutory expenses and all other discretionary expenditures. If the government fails to impose discipline, increase domestic income, or reduce spending (or both) to generate fiscal space, it will be forced to seek assistance from an International Monetary Fund program.

Several foreign credit rating organizations have recently downgraded Ghana's economy, citing its inability to generate enough cash to cover its debt. This signal to investors is that Ghana's government bond is unprofitable, and its default risk is too high.

This implies that the government may be unable to raise funds on the international financial market. The alternatives are either to borrow domestically, drive out the private sector, or borrow from other nations. If this option has been exhausted, the country must apply for a program via the International Monetary Fund.

What effect has this had on the economy?

As a result of the country's massive public debt and sluggish income growth, it must borrow to support its expenditures. Until the government borrows funds, it is essentially powerless. This has impeded the government's capacity to execute its plans and policies for economic growth, transformation, and job creation.

Over 16 years (2006-2021), the extractive industry was the primary driver of the country's economic development. This industry is capital-intensive, employing more machines than people. The result is that, while there is some economic growth, it is not derived from employment-generating areas of the economy. This is the reason why unemployment has soared4 from 5% to 13%.

Exit possible solutions?

Ghana is now in a precarious situation. The only solution is to generate sufficient income to fund its development. Even if the government could borrow, it would still need to boost domestic income to pay down the debt. Therefore, there is no alternative for mobilizing domestic resources. $6 billion is the expected budget shortfall for 2022. The government must collect money via taxation (without overburdening taxpayers) and other means.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies conducted research1 on the government's income streams in 2018 and produced the following suggestions for future yearly revenue increases for Ghana's public finances:

· Tax exemptions – $790 million

· 55% share of the extractive sector – $4 billion

· Personal income tax of the workers in the informal sector – $47 million

· Property tax – $157 million

According to the Ghana Statistical Service, there are about 7.7 million informal sector employees, although it is difficult to determine their salaries. There are difficulties in taxing unknown revenues. Therefore, there seems to be a solid economic case for taxing them using the suggested e-levy3. But the tax must be devised to fulfill the goal of taxing the revenues of informal sector employees.

In addition to generating more money, the government must close all financial loopholes and maintain sound fiscal management. In their findings, the Auditor General's office and the Parliament's Public Accounts Committee often highlight financial irregularities.

The latest Auditor General's report2 uncovered around $1.8 billion in public budget violations. When these inconsistencies are rectified, the administration will acquire the trust and support of the populace.

If the nation's public debt continues to increase at its present rate, it is likely to experience a financial crisis, which might need a rescue from the International Monetary Fund.

Reference

[1] The Role of the Extractive Sector in Ghana’s Comparatively Low Public Sector Revenue Mobilization [Policy Brief No.11] . Available at https://www.ifsghana.org/the-role-of-the-extractive-sector-in-ghanas-comparatively-low-public-sector-revenue-mobilization-policy-brief-no-11/

[3] Duho, King Carl Tornam, Stephen Asare Abankwah, Gabriel Azu, Duke Ayim Agbozo, Vincent Seny Duho, and John Selorm Atigodey. "Central Bank Digital Currency in Ghana, the e-Cedi: Disruptions, Opportunities, and Risks." Dating Policy Brief 6 (2022).

[4] Ghana Unemployment Rate Has Tripled in 10 Years, Census Shows. Available at:

[5] Aduhene, David Tanoh, and Eric Osei-Assibey. "Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on Ghana's economy: challenges and prospects." International Journal of Social Economics (2021).

[6] Songwe, Vera, and Christine Awiti. "African Countries’ Debt: A Tale of Acceleration at Multiple Speeds and Shades." Journal of African Economies 30, no. Supplement_1 (2021): i14-i32.